Crystal Woodward

Artist Statement:

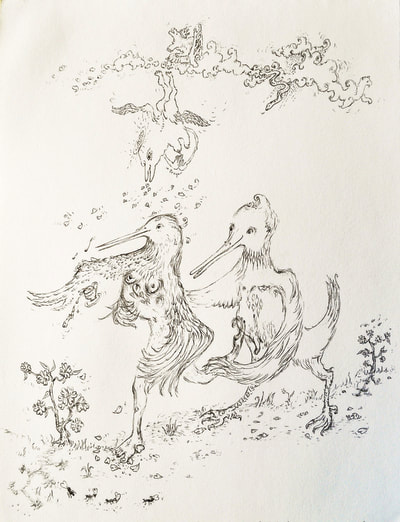

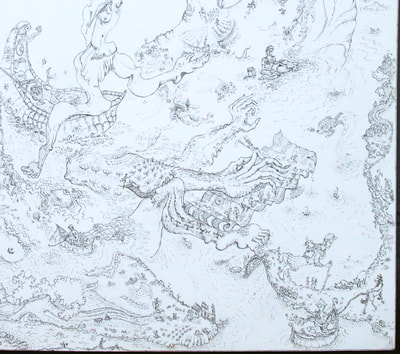

Early in life, one encounters treasures of the natural world, and thus begins the weaving together of imagination and reality into the magic carpet of artistic creation. From a child, I was involved in painting, drawing, and sculpture, and continue to this day in these media. I was also interested in different countries and cultures. While living in London in the late 1960s, I explored insertions of text into structured, architectural contexts reflective of human personalities. In my drawings of those years, my “calligraphies”—language-like markings—were expressive of a sense of seeking a language, and an awareness, not just human: words could be multidimensional, embodying the voices and elusive meanings of objects and spaces and of other life forms, as well as of other people. Subsequently, in southern France, in the Luberon area, I was struck by the landscape, inhabited and fashioned over generations by a local farming tradition. This context gave an anthropological grounding to my interests in languages other than verbal, and was catalytic to my developing, in the late 1970s, a specific “Art as Visual Language” approach, to bridge gaps, between words and images, self and other, observed reality and imagination. Its sequence of structured steps, alternating with walks in landscape, are a vehicle for rounding up fleeting moments of perception and thought, and for bringing them into my art.

I also evolved a Landscape Alphabet, which I use to transcribe poems I’ve written into my drawings. As well, my works on paper and canvas are often quick and “free”, with neither of the Visual Language approaches.

The landscape in France, as well as other landscapes, was an incentive to becoming involved in photography. Walking through the landscape, I am struck not only by the aesthetic and cultural richness, but also by the cognitive challenge: different views have intriguing correspondences, echoes of shapes and forms, geometric patterns, interwoven levels of terraced hillsides. This prompts my taking a series of photos of the same place over time, as well as of the people who work such landscapes.

Drawing and painting, and photography, for me are interrelated; for example, in the drawings one may find views seen in the photos too. However, the drawings are not done from photos, rather from the lived experience of spending many hours outdoors. In the drawings, human figures, often couples, reflect this close relationship with landscape, sometimes they are even partly constituted of landscape elements.

My photographic work has also been involved in goals of landscape/cultural heritage/biodiversity preservation, in publications and exhibits.

Early in life, one encounters treasures of the natural world, and thus begins the weaving together of imagination and reality into the magic carpet of artistic creation. From a child, I was involved in painting, drawing, and sculpture, and continue to this day in these media. I was also interested in different countries and cultures. While living in London in the late 1960s, I explored insertions of text into structured, architectural contexts reflective of human personalities. In my drawings of those years, my “calligraphies”—language-like markings—were expressive of a sense of seeking a language, and an awareness, not just human: words could be multidimensional, embodying the voices and elusive meanings of objects and spaces and of other life forms, as well as of other people. Subsequently, in southern France, in the Luberon area, I was struck by the landscape, inhabited and fashioned over generations by a local farming tradition. This context gave an anthropological grounding to my interests in languages other than verbal, and was catalytic to my developing, in the late 1970s, a specific “Art as Visual Language” approach, to bridge gaps, between words and images, self and other, observed reality and imagination. Its sequence of structured steps, alternating with walks in landscape, are a vehicle for rounding up fleeting moments of perception and thought, and for bringing them into my art.

I also evolved a Landscape Alphabet, which I use to transcribe poems I’ve written into my drawings. As well, my works on paper and canvas are often quick and “free”, with neither of the Visual Language approaches.

The landscape in France, as well as other landscapes, was an incentive to becoming involved in photography. Walking through the landscape, I am struck not only by the aesthetic and cultural richness, but also by the cognitive challenge: different views have intriguing correspondences, echoes of shapes and forms, geometric patterns, interwoven levels of terraced hillsides. This prompts my taking a series of photos of the same place over time, as well as of the people who work such landscapes.

Drawing and painting, and photography, for me are interrelated; for example, in the drawings one may find views seen in the photos too. However, the drawings are not done from photos, rather from the lived experience of spending many hours outdoors. In the drawings, human figures, often couples, reflect this close relationship with landscape, sometimes they are even partly constituted of landscape elements.

My photographic work has also been involved in goals of landscape/cultural heritage/biodiversity preservation, in publications and exhibits.

Artist Bio:

Crystal Woodward developed a specific “Visual Language” approach and a “Landscape Alphabet”. Her drawings reveal couples, situations, and poems constituted of landscape elements such as vineyards, brooks, and clouds, while her photographs add views sometimes matching perspectives in the drawings, and celebrate the beauty of landscapes such as of the Luberon Mountain region of southern France.

In her work, superimpositions, ambiguities, and distortions are expressive of the inner meanings and motions of experience (thoughts, feelings, corporeal sensations, etc.) within the self-world relationship. Body-landscape interweavings, and their meetings across spaces, show – and, by way of the humor arising in a multitude of situations, bring to life – a principle germinal to all creation, or “co-creation” , that of the conjunction of opposites.

Regarding this dimension of “co-creation”, Crystal points to the paysan farmers as they work the cultivated landscape with the seasons, with the earth and terrain, and with the knowledge and gestures of ancestors passed down over generations. A co-creative attitude has parallels in art, as well as in science and other disciplines, where it can be conducive to imagination, and possibly to a more sensitive relation to other persons, cultures, and modes of being.

One viewer commented, “Word and poem, drawing, and the photographer’s eye, all are welling up from a similar place—the experience of landscape. Crystal’s work evokes a layered density of story-telling.” Whether or not there’s actually a poem inserted, viewing one of her drawings is rather like reading a text; for in the landscape itself one discovers elements suggestive of writing – an air current around a suspended feather (a plume), the furrows of a plowed field, rivulets in a brook -- , all these may be a language, a writing ... expressive of numerous voices who inhabit these spaces. Who is the artist, and who the author, of a drawing or poem? Do we create, or co-create, and share in meaning with others?

Accordingly, Crystal’s photographic work has been in part been directed toward preservation of landscape, cultural heritage, and biodiversity, through slide lectures, teaching, publications, and exhibits.

Crystal Woodward developed a specific “Visual Language” approach and a “Landscape Alphabet”. Her drawings reveal couples, situations, and poems constituted of landscape elements such as vineyards, brooks, and clouds, while her photographs add views sometimes matching perspectives in the drawings, and celebrate the beauty of landscapes such as of the Luberon Mountain region of southern France.

In her work, superimpositions, ambiguities, and distortions are expressive of the inner meanings and motions of experience (thoughts, feelings, corporeal sensations, etc.) within the self-world relationship. Body-landscape interweavings, and their meetings across spaces, show – and, by way of the humor arising in a multitude of situations, bring to life – a principle germinal to all creation, or “co-creation” , that of the conjunction of opposites.

Regarding this dimension of “co-creation”, Crystal points to the paysan farmers as they work the cultivated landscape with the seasons, with the earth and terrain, and with the knowledge and gestures of ancestors passed down over generations. A co-creative attitude has parallels in art, as well as in science and other disciplines, where it can be conducive to imagination, and possibly to a more sensitive relation to other persons, cultures, and modes of being.

One viewer commented, “Word and poem, drawing, and the photographer’s eye, all are welling up from a similar place—the experience of landscape. Crystal’s work evokes a layered density of story-telling.” Whether or not there’s actually a poem inserted, viewing one of her drawings is rather like reading a text; for in the landscape itself one discovers elements suggestive of writing – an air current around a suspended feather (a plume), the furrows of a plowed field, rivulets in a brook -- , all these may be a language, a writing ... expressive of numerous voices who inhabit these spaces. Who is the artist, and who the author, of a drawing or poem? Do we create, or co-create, and share in meaning with others?

Accordingly, Crystal’s photographic work has been in part been directed toward preservation of landscape, cultural heritage, and biodiversity, through slide lectures, teaching, publications, and exhibits.

Artist email: [email protected]